- Overview: Breast Tissue Changes

- How Are Benign Breast Conditions Detected?

- Nipple Discharge

- Lobular Carcinoma in Situ (LCIS)

- Fibrocystic Breast Condition

- Simple Cysts

- Galactoceles

- Fibroadenomas

- Phyllodes Tumors

- Intraductal Papillomas

- Granular Cell Tumors

- Duct Ectasia

- Fat Necrosis

- Breast Inflammation: Mastitis

- Conclusion

- Additional Resources and References

A benign breast condition is any non-cancerous breast abnormality. According to the American Cancer Society, when breast tissue is examined under a microscope some type of abnormality is common in nine out of every ten women. Though not life-threatening, benign conditions may cause pain or discomfort for some patients. Some (not all) benign conditions can signal an increased risk for breast cancer. The most common benign breast conditions include fibrocystic breast condition, benign breast tumors, and breast inflammation. Depending on the type of benign breast condition and the patient's medical situation, treatment may or may not be necessary.

The breast is composed of two main types of tissues: glandular tissues and stromal (supporting) tissues. The glandular tissues house the milk-producing lobules and the ducts (the milk passages). The stromal tissues include fatty and fibrous connective tissue. Any changes in the glandular or stromal areas may cause symptoms of benign breast conditions.

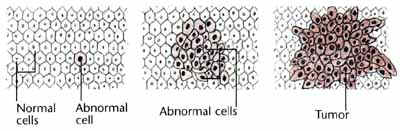

Some women experience changes to their breast tissue over their lifetime. These changes can include an increase in the number of breast cells (hyperplasia) or the emergence of atypical breast cells (atypical hyperplasia). In some instances, a portion of breast tissue that exhibits abnormal characteristics can eventually develop into a cancerous tumor. That is why physicians carefully monitor patients with abnormal breast cells, to ensure that if cancer develops at a later date, it is detected and treated early. Some patients with atypical hyperplasia may also be recommended to take the drug tamoxifen to help prevent breast cancer. While the appearance of atypical hyperplasia increases the risk of breast cancer, not all women with abnormal breast cells go on to develop breast cancer.

The following chart summarizes the typical progression of breast tissue from "normal" to "cancer:"

Courtesy of the American Medical Association.

While many cases of breast cancer arise from the above sequence some breast tumors may skip one or more intermediate steps (for example, cells may proceed from "normal" directly to "carcinoma in situ"). In general, anything farther along than atypical hyperplasia is usually classified as a cancer. Abnormalities beginning withductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), usually require treatment as cancers. The treatment of benign breast conditions varies depending on a number of factors including the exact diagnosis, potential for developing breast cancer, and a woman’s discomfort.

Benign breast lumps are often first detected by physicians during clinical breast examination, routine mammogram or by patients practicing breast self-examination (BSE). Focal pain (pain confined to one spot in the breast) or nipple discharge (other than milk) may also alert a woman to have her condition checked by a doctor. Benign breast lumps are usually confirmed by imaging tests (mammogram, ultrasound/sonogram), observing the lump over a period of time, or doing fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB), core needle biopsy (CNB) or surgical biopsy.

Nipple discharge, fluid coming from the nipple(s), is the third most common breast complaint for which women seek medical attention, after lumps and breast pain. The majority of nipple discharges are associated with non-cancerous changes in the breast such as hormonal imbalances or papillomas (see section below on intraductal papilloma for more information). However, because a small percentage of nipple discharges can indicate breast/nipple cancer, any persistent discharge from the nipple(s) should be evaluated by a physician.

Up to 20% of women may experience spontaneous milky, opalescent, or clear fluid nipple discharge. During breast self-exam, fluid may normally be expressed from the breasts of 50% to 60% of Caucasian (White) and African-American women and 40% of Asian-American women. Usually, a discharge that is clear, milky, yellow, or green, and is noted from both nipples, is not associated with breast cancer. Bloody or watery nipple discharge, especially if limited to one side and/or a single breast duct, is considered abnormal; however, only around 10% of abnormal discharges are found to be cancerous.

Nipple discharge may be a concern if it is:

- Bloody or watery (serous) with a red, pink, or brown color

- Sticky and clear in color or brown to black in color (opalescent)

- Appears spontaneously without squeezing the nipple

- Persistent

- On one side only (unilateral)

- A fluid other than breast milk

Women should report persistent nipple discharge to their doctors for analysis. To examine nipple discharge, a small amount of the fluid is placed on glass slides under a microscope to determine if cancer cells are present.